When I was a new and shiny graduate from the AECC maybe less than five years old, if patients told me the GP had diagnosed them with gout, I would have accepted it, no questions asked.

But I learned that it’s always a good idea to actually check the symptoms fit the diagnosis and to make sure a blood test has actually been done to confirm raised uric acid.

Quite a few times, it turns out, the symptoms sounded nothing at all like gout and there was no blood test.

But they were stuck on an NSAID and allopurinol regardless, and months later, there they remained.

So when my mum told me the GP had diagnosed her with gout, I was suspicious, to say the least.

But there it was a red-swollen first metatarsal phalangeal joint and raised uric acid on her blood test.

My Mum has had some health concerns over the years and, as a consequence, at this point in time, was taking several blood-pressure medications (NOTE: since this incident she is no longer diabetic and takes 1/2 the dose of one blood pressure medication, when she was previously on three plus metformin, I talk about that here ????

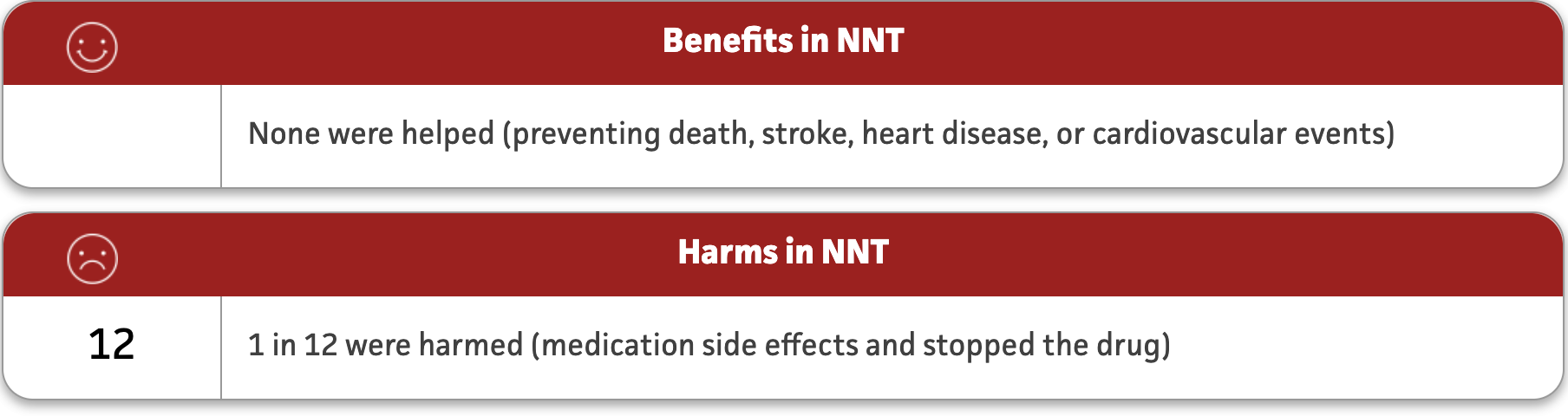

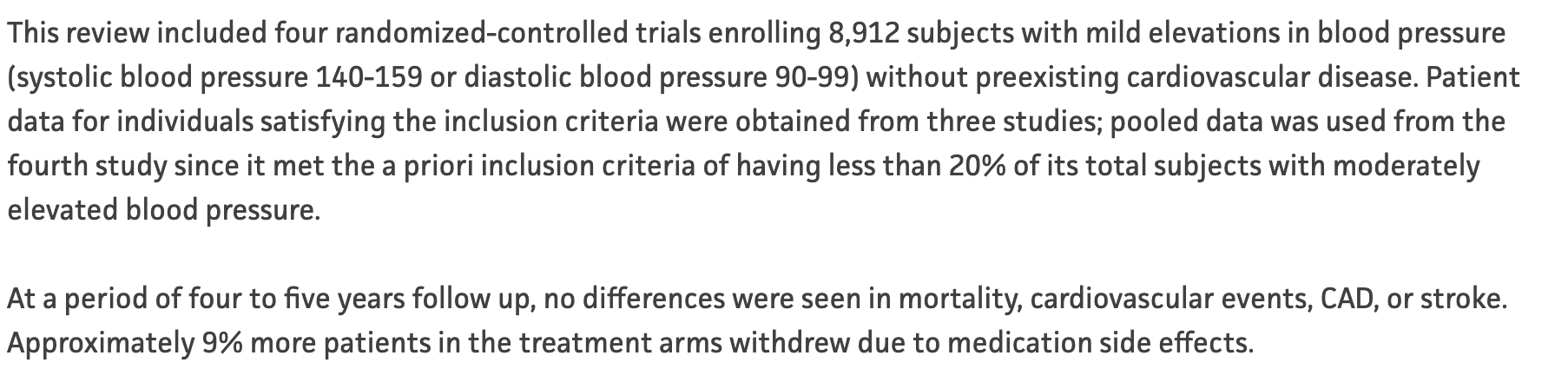

It is worth pointing out that, according to research, if you bring blood pressure down from 150-159/90-99 for primary prevention, they get zero overall improvements in cardiovascular events, none.

But 9% chance of harm by side-effects.

I would argue that what used to be considered natural aging is now considered a “disease”.

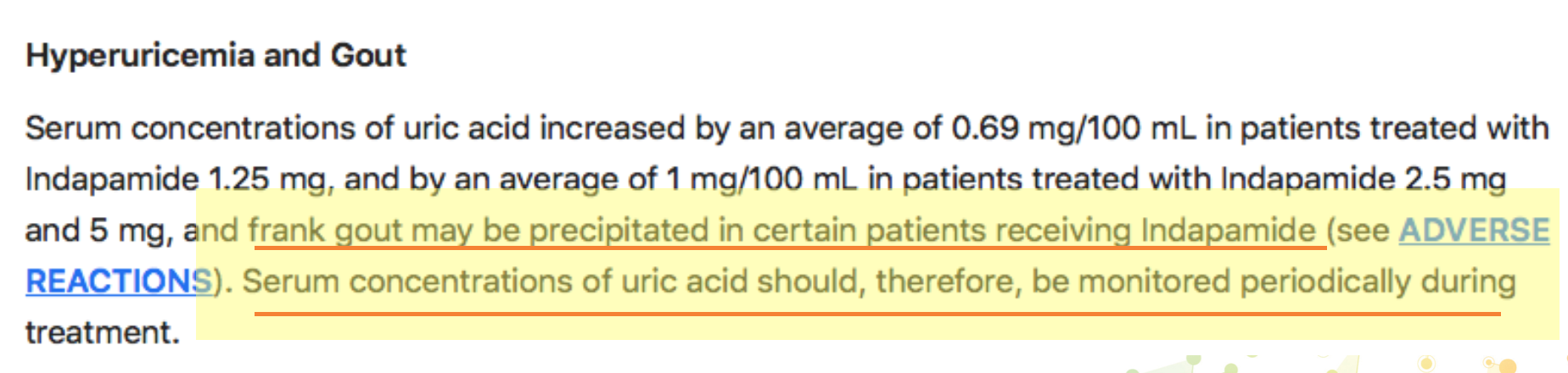

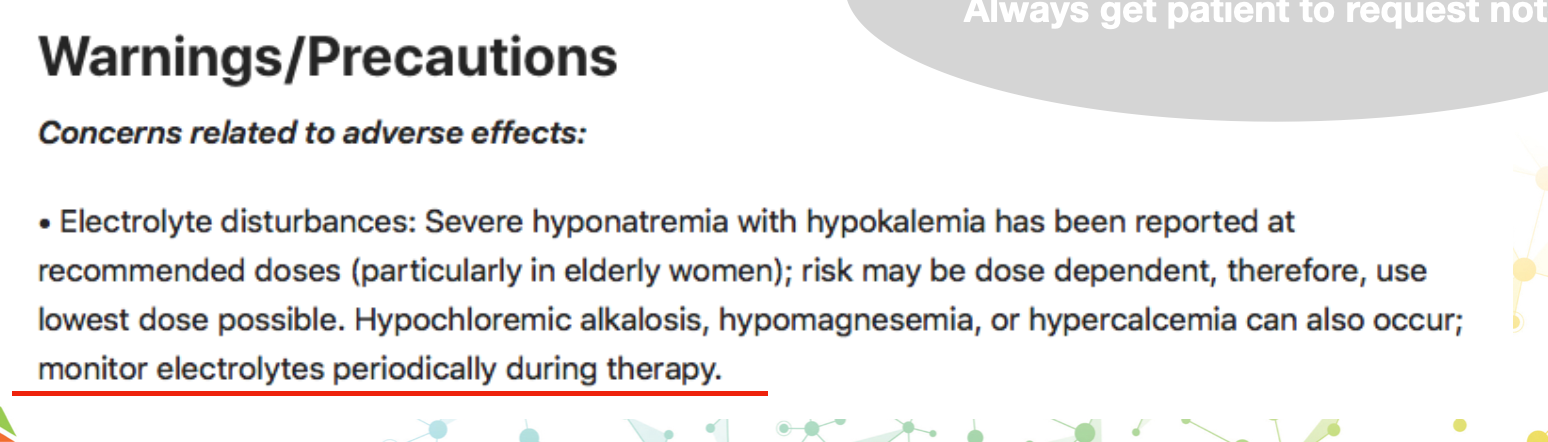

Anyhoo……in this case it turns out that one of the drugs, indapamide, raises uric acid and thus can cause gout.

This is well known and GP’s should be monitoring uric acid levels AND also potassium levels.

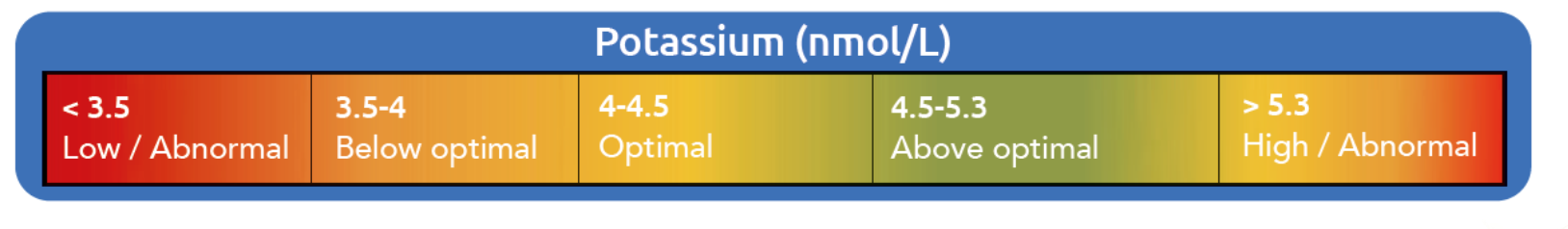

But this doesn’t always happen (hence why you should ALWAYS get the patient to request their blood tests and check it), plus, the NHS has a very wide range of “normal”, and we want optimal and to spot a trend down before frank hypokalaemia.

For me, I like to see it between 4-5 mmol/L, NHS is interested if it drops below 3-3.5 mmol/L ish depending on the lab.

Gout is pretty easy to spot, but as potassium is a key electrolyte involved in a lot of neurology & muscle control, it can be a much more insidious, vague onset and hard to spot.

Also, low intake of potassium is very common, 98 % of Americans don’t meet the recommended daily intake.

It is mainly found in fruit and vegetables, and let’s face it, some of our patients think chips count as one of their five a day (FYI it should be 8 veg a day, minimum if you want minerals that way).

So, with an NRV/RDA of around 2g (2000 mg, note optimal is possibly 3-4g) it can be quite hard to keep levels optimal.

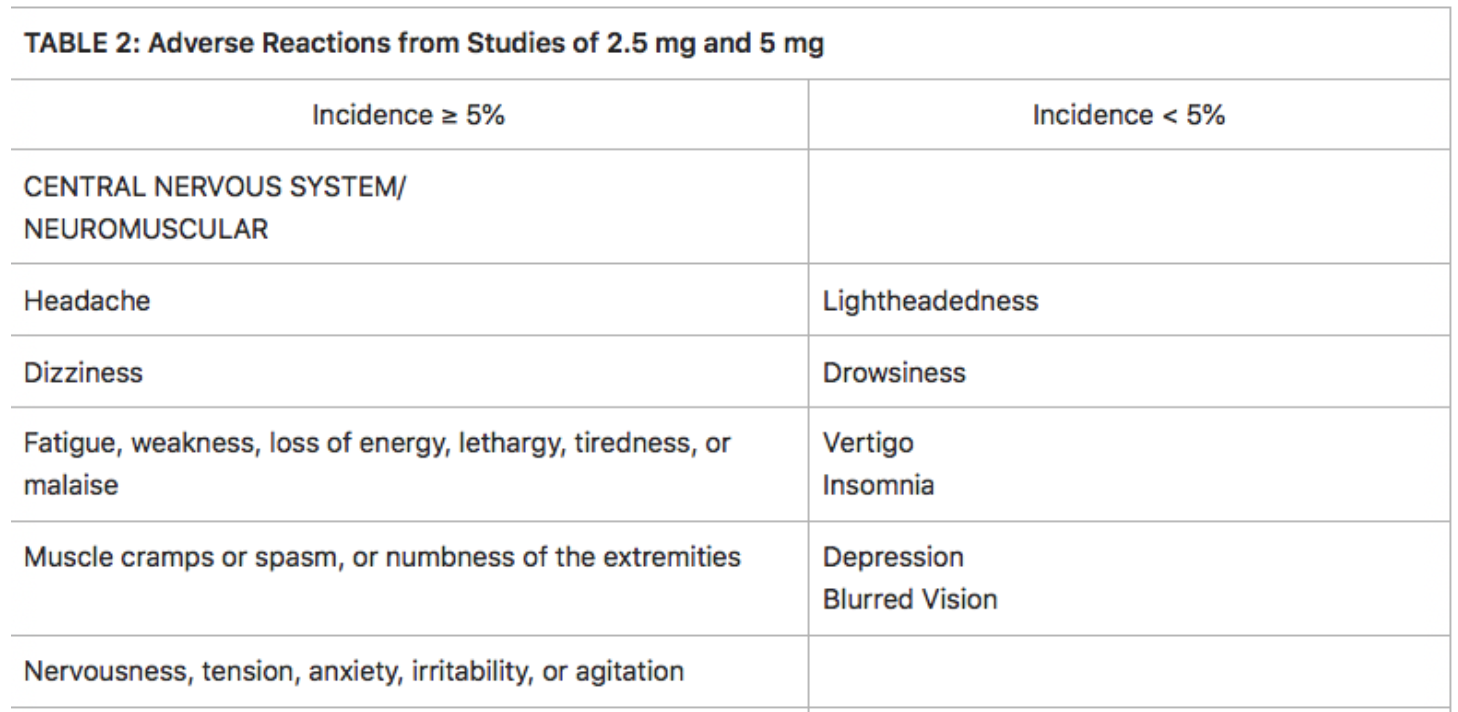

The symptoms of low potassium can include:

Weakness and fatigue

Muscle cramps

Digestive problems – bloating and constipation (less bowel muscle contraction)

Heart palpitations/arrhythmia (how ironic)

Muscle aches and stiffness

Tingling and numbness

Mood disorders (up to 20% of patients had potassium deficiency in one study of acute psychiatric patients)

If you look at the side effects list on indapamide you will see there is a lot of overlap.

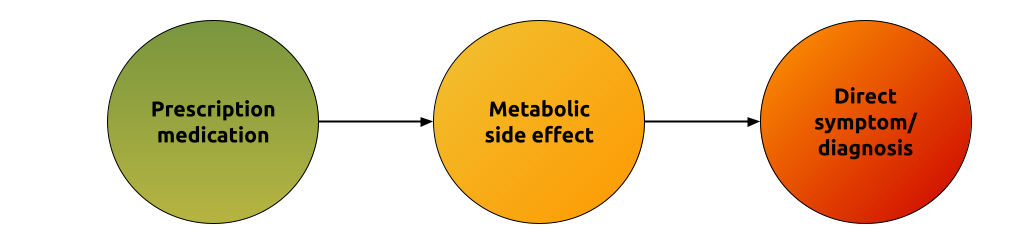

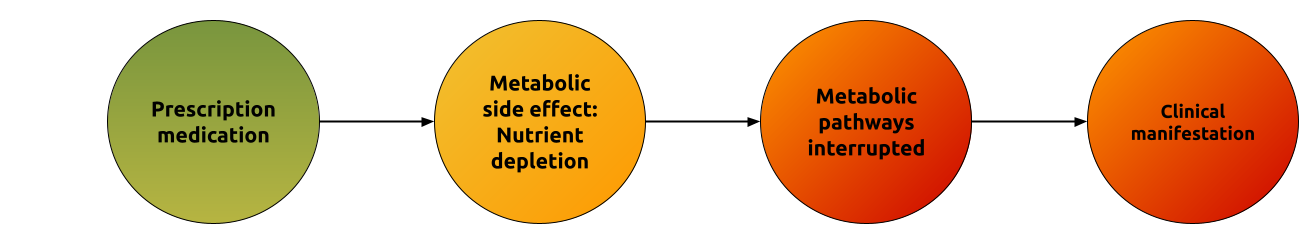

This is a really important concept.

When you look up drug side effects they occur because of a deficiency-induced by the drug or the drug inhibits something or is toxic in some way.

Example, some drugs directly affect you, like NSAID’s.

Or they do it indirectly, like a PPI for stomach acid.

Thus, we can, in many but not all cases, stop or reduce the side effects by supplementing and changing diet.

If you need to use potassium as a supplement, ideally use citrate, it is cheap and also alkalinises the tissues too (we are in R&D right now with an electrolyte formula based around potassium citrate, salt and magnesium).

I usually suggest around 1000 mg daily and make sure they ask the GP to retest the levels at some point.