Tony Blair has quite the legacy.

Leaving aside his penchant for starting illegal wars, one of his biggest changes was to flood GP’s surgery with money (1 billion to be exact).

Around 2004 he introduced “payment by performance” via the quality and outcomes framework (QOF), a method for monitoring the quality and outcomes of medical intervention.

This resulted in a 50% pay rise for GPs (with less hours), but they were hitting their targets even higher than anticipated and so the treasury had to fork out another 400 million.

So they tightened the screw and for higher “targets” to reach for.

Tricky bit is those targets are surrogates for health, but not actually health per se.

Thus, war was declared on cholesterol, blood sugar levels and blood pressure, this was the age of prevention.

So from 2004 prescriptions for cholesterol lowering medication went up around 700%, over 200% for diabetes and nearly 300% for “high” blood pressure.

So what is the end goal of these colossally expensive medications?

It must be to reduce death and morbidity, otherwise what is the point?

Plus we need to take into account the side effects of medications and be cognisant of drugs interacting in the so called poly-pharmacy (they do not test medications in combination generally).

Thus we could ask how preventative are preventative drugs?

And we could ask patients what % reduction in risk of death they would expect from a preventative drug and at what % would they decide the benefit was not worth it?

This is exactly what Trewby et al examined.

But before we dig into the methods and results, let’s just re-cap on statistics (I’ll make it easy, I promise).

Let’s pretend we have 100 people who have never had a heart attack (primary prevention) and they all take a statin to lower their “high” cholesterol.

And another matched group who took a placebo.

At the end of 5 years, we analyse how many died of all causes, excluding trauma.

That way, we can include potential side effects killing us by things other than heart disease, and if there is a reduction in heart attacks and that does reduce death, we should see it.

Note that drug companies will generally use heart attacks on their own as their only marker for “success” for obvious reasons i.e. if the statin gave them cancer, you can remove them from the study and your % are still good.

So let’s say that the placebo group had 3 heart attacks.

So, straight away, the challenge here is they had a 97% chance of being just fine with no intervention.

Or put another way, even if they took the real drug, and it was 100% effective in every case (never going to happen) they will have a 3 % chance of benefitting from the drug – pretty poor odds.

In the statin group, let’s say it dropped to 2 heart attacks.

We would call this a 1 % ABSOLUTE risk reduction (3% down to 2% is a 1% drop)

You could also use another statistic called the number needed to treat (or NNT) which means how many people were treated to stop one “event”, in this case, a heart attack.

In this scenario, you would need to treat 100 people for 5 years to stop one heart attack, thus statins would have an NNT of 100.

But the reality is it’s a hard sell to patients (and Doctors) which is what we will see later in the study by Trewby.

And bear in mind we are still using one heart attack as the end point, not death of all causes excluding trauma.

So the drug companies use a different way of expressing the results, a way that is far more impressive to everyone.

They argue that if you are in the 3% group that would have had a heart attack, then the reduction from 3% down to 2% is RELATIVELY a third and thus a 33% RELATIVE risk reduction.

All of a sudden we are looking pretty impressive, aren’t we?

But the reality is, this is a meaningless statistic.

Patients cannot know if they are in the 3% heart attack group or the 97% group that had no issues and, so in my opinion, this is a deliberately misleading statistic.

Sadly, this is the basis for the regulatory approval and sale of almost all preventative drugs that are taken.

Even the single digit figures of absolute risk reduction are for heart attacks instead of all cause mortality, because when you use the latter often the benefits disappear all together (likely due to side effects from the drug).

Let’s go see what patients think with Trewby.

307 people in 3 groups:

Group 1: Recently discharged from cardiac unit on meds

Group 2: On meds, no cardiac history

Group 3: No meds and no cardiac history

They were asked to consider if their cholesterol was high and they were offered a “safe drug” which could help reduce the chance of a heart attack.

Note not death of all causes.

This is important because they told them the drug was “safe”. Thus, they are not considering any risks of taking the drug, so this is a slightly unfair question, in my opinion, which increases the chances of people agreeing to take drugs.

They used the diagram below.

They were subsequently interviewed, and they wanted to know if the chance of benefit was less than 5% (absolute risk reduction) how many people will still take the “safe drug”.

Not surprisingly, the recently released from cardiac unit group had a higher % at 32.4, while the healthy and on no meds (group 3) were at 21%.

From my point of view, there is still a bizarrely high figure in groups 2 and 3. I wonder if that is partly due to the lack of risks being discussed and the lack of alternatives being presented.

Weird, crazy stuff like regular exercise and real, whole food, that kind of thing.

Regardless, given the majority of patients are taking statins for primary prevention, if patients were presented with facts in an understandable way, we would be looking at 80% less prescriptions for statins.

But in reality, the 5% is larger than the actual benefit from statins, even for heart attack, not even all cause death.

The figures for that vary depending on who you read. If you read independent reviews, they are much lower.

It is worth pointing out that the studies have been critised for only running for five years. People like Peter Attia, point out that patients on statins do not take them for five years, it is for life. Thus, he argues that the benefits multiply over the years.

And he has a point, however, so do the side effects, which are not insignificant and are downplayed and minimised by the pharmaceutical industry and GP’s.

From the www.thennt.com site, see what they say about people with low risk of heart attacks, presented as an NNT, both heart attack fatal and non-fatal plus all cause mortality.

or as a %:

I am pretty sure the average patient with no history of heart issues, given a % benefit over 5 years (as that’s what we have now in terms of data) of 0.5% reduction in risk of heart attack is not going to get them gagging to cash in that prescription.

And if the GP points out the more useful end point of all cause mortality (excluding trauma), of 0% benefit, I think it would seal the deal of no prescription.

But let’s give the drug companies a chance to shine. Let’s see how preventive statins are in people that have already had a heart attack.

By definition, they must have a much higher chance of stopping heart attacks (and death), right?

Well, kind of, but the benefits are still thinner than my hairline.

Or as a %:

Note, the owners of the NNT who run it free as a service, have it in GREEN saying this is a good return on investment.

That is how low the bar is set for positive benefits from medication, a 1.2% reducton in death.

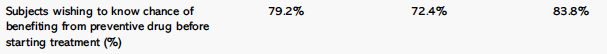

One really odd figure from the study is below:

Around 20% ish of patients simply did not want to know the chance of benefitting from the drug, how strange!

This ties in with another fascinating finding that suggests patients have a remarkable degree of faith in their GP’s.

When asked if they would take the same drug if recommended by their GP, the figures go up dramatically.

More than doubling across the board, from 21% in the healthy group to 56%!

The tragedy of this, in my opinion, is patients believe that GP’s are operating in a vacuum that is independent of finances and reward.

The reality is they get paid to reduce cholesterol.

Yes, they could give diet and lifestyle advice in the 8-12 minutes they have and hope the patient sorts out a lifetime of bad habits.

But why risk missing out on your bonus when you can just give them a statin and know it will come down?

This is all tragic for both the patient who is paying for poor care and the GPs, who now have relatively little autonomy and are now more akin to pharmacists with medical degrees.